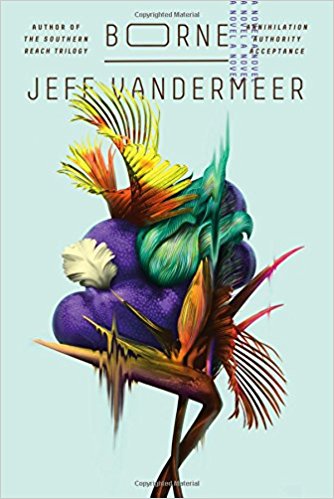

Borne

Reviewed Aug 4, 2017 on The Litt Review.

I read this book as part of the awesome-scifi reading group, and came to the book with no preconceptions or ideas on what it was about. Someone suggested I read it, so I bought it, flopped down on the couch, and opened the pages. This may be one of the most delightful ways to start a book.

Borne is strange. It’s from the point of view of a scavenger in a ruined, post-apocalyptic city-scape dominated by a giant eggshell like building where The Company was housed, and out of which come monsters and biotech. Humans live on the fringes - scavenging for food in the wastes, looking for old protein bars, dead dogs, and - strangely - alcohol minnows.

The girl found a couple of dried-out alcohol minnows by their dull glint and shoved them in her satchel. A few drops of water might revive them, but first she’d have to decide if those drops were more valuable to drink.

Your guess is as good as mine, but they sound delicious. In this, I was reminded of Watermelon Sugar by Brautigan. The landscape of the book is surreal, and we have to take it for granted that life can exist this way. Creatures are often not what they seem - foxes may be biotech androids, lightning bugs are actually lightbulbs, an ever-burning fire is a Flintstone-esque satisfied creature, reminiscent of the demon from Howl’s Moving Castle.

In this city, we come across beautiful passages, too, which are either Lovecraftian in their horror, or like Poe in their poetry.

I came to the edge of a courtyard and a peculiar sight. For anywhere but here. Three dead astronauts had fallen to Earth and been planted like tulips, buried to their rib cages, then flopped over in their suits, faceplates cracked open and curled into the dirt. Lichen or mold spilled from those helmets. Bones, too. My heart lurched, trapped between hope and despair. Someone had come to the city from far, far away – even, perhaps, from space! Which meant there were people up there. But they’d died here, like everything died here. … they were planted here now and grew strangeness from their faces, and I didn’t trust them.

The apocalypse, give or take a few minor missing creature comforts, doesn’t sound so bad.

Oh, did I mention yet that the city is overrun by fire-breathing, poison-clawed bears. And mutant kids with bug eyes. And one particularly massive god-bear, Mord? Guess not. Well. That’s also true. And it’s ridiculous. At times I went from smiling with incredulity, to really believing that Mord was flying over my own cityscape, too. That the entire book isn’t a concession to joke literature is because of the strength of the prose.

Some part of me could not decide if I was witness to the passage of a god or, perhaps, out of hunger, a hallucination. But in that moment I wanted to hug Mord. I wanted to bury myself in his fur. I wanted to hold on to him as if he were the last sane thing in the world, even if it meant the end of me.

It would be hard to take this sentiment as anything but serious, because it is so human, and so bizarre. By making the world ridiculous, Vandermeer makes it seem close.

And into this maelstrom comes Borne, an amorphous squid-like thing that the narrator teaches to talk and live. Much of the book is taken up with understanding what Borne actually is. There’s no clear answer, by the end. And, naturally, there’s also no clear answer as to what Mord is, or what the Company is, or whether the world is this one or another, or who the main two humans we know are. Or whether memories are real.

“How do you know it happened?” he asked. “Is it written down anywhere?”

How did I know it had happened? Because of its absence now, because I still felt the loss of it, but I didn’t know how to convey that to Borne then, because he had never lost anything. Not back then. He just kept accumulating, sampling, tasting. He kept gaining parts of the world, while I kept losing them.

This balance - between knowing and not knowing - pervades the book. In one of the best passages, Vandermeer manages to ask this question even while describing surgical slugs.

Wick had already closed up my wounds with the help of surgical slugs. I remembered the cool-cold sensation of their progress from the last time I had suffered an injury. My attackers had been creative, had cut me in patterns, writing words that had no meaning to anyone, least of all them. And so the movement of the slugs had retraced those paths, those words, given them a meaning by accident.

Readers of science fiction get used to dealing with unreality, pretty fast. Bladerunner as a film is so strong not because of answers it offers about what humanity means, but because of questions it poses to the interested watcher. Is Decker an android himself? What is the significance of folded unicorns? (Is there a parallel universe where the Detective Gaff is in fact Admiral Adama?) I’d consider Borne to be also adept at this. It self-referentially admits that the book itself may be unreliable in answering questions, anyway.

I’ve brought you in late. I can only recite what were hauntings. He could be kind. He could be thoughtful. He could be idealistic. That’s what I know.

There were shortcomings. For one, I felt the whole giant-possibly-mechanical-flying-bear thing was stolen straight out of one of the worst books I’ve ever read, The Dark Tower series by Stephen King. I’m unapologetic in saying that entire series was complete crap. As well, I didn’t really understand or get the significance of borne as the title and the name of squiddy. Yes, he was carried, and it rhymes with born, and it is reminiscent of a river. But that’s just clever word play. It doesn’t really help me feel the world more. And the most obvious Fitzgerald reference of all time, “While the river continued on its course, carrying all of us with it,” at the end of one of the books, came off as heavy-handed pretension.

The vocabulistics in this book were not literary-grade, either. It’s written in clear and concise prose, but using the rare word carious in the first passage came off as an attempt to be literary, which wasn’t matched elsewhere. That’s just my opinion, and it is biased, because that’s the only word I circled in the entire book. Your mileage may vary on this small point.

Of course, I was able to ignore these issues, because it was just a delightful book. I laughed out loud on occasion:

Wrote Borne in his journal: “My earliest memory is of a lizard pooping on me and ever since I have hated lizards for ruining my first memory. But I also love them because they are delicious.”

There was also wonder:

But Borne kept flattening and widening the aperture at the top of his body until he resembled an enormous passionflower blossom. Complex and beautiful, with many levels.

Have you seen a passionflower? They’re beautiful.

And, finally, the book was good because it mattered, to me. Near the finale, we get to ponder the fate of other worlds, and the question of where the story takes place.

Was there a world beyond? Is that what the shining wall of silver raindrops meant? A gateway? Or is that a delusion?

It doesn’t matter. Because now we can make one here.

A world.

I disagree that it doesn’t matter. Other worlds matters because we ask them if they’re there. In asking, we create them. In creating them, we have something to refer to, to ask ourselves where it is we live now. “Humanity doesn’t want other worlds - it wants a mirror,” as Solaris reminds us.

Borne was a beautiful mirror to look into.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.