Finn and Hengest

Reviewed Sep 19, 2019 on The Litt Review.

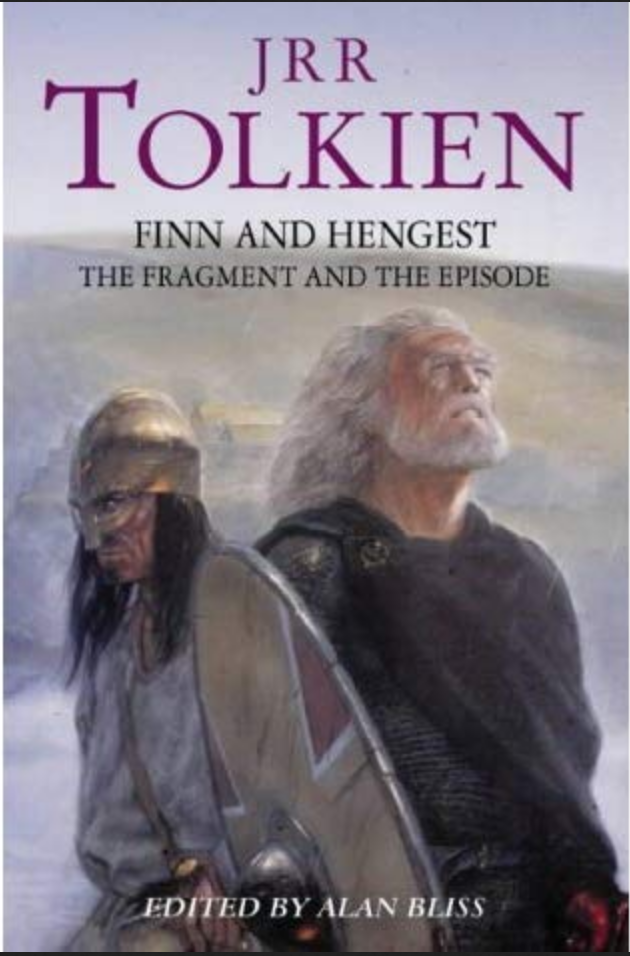

Finn and Hengest had a sweet cover of two men, one seemingly crying into the wind and driving rain, and another looking cunningly askance, while behind them some Heorot sat on the throne of a hill above the raging sea. I was sold immediately (as was the book). Unfortunately, the drama of the cover was more moving than the text, such as it was. The book was a jumble. There was a preface, an introduction, and then the two texts which the book was to be based on, presented in their original Old English (one a stand-alone fragment, and the other a few hundred lines from Beowulf). This was followed by a ‘Glossary of Names’ which took up a third of the book, followed with some brief commentary, before the fragments presented in the first section were finally translated at around 95% through the book. Then, a reconstruction of how the actual story might have gone, with some rather obscure appendices to top the whole thing off.

I think it should have been structured with the Reconstruction at the beginning, perhaps followed by the translations. As it was, reading this book straight through felt like entering a dark forest in northern Germany in 500 a.d.. However, once in that forest, instead of conjuring images of strange men fighting in the mist, the book makes you swat scribal midges, pull your shoes from the caesuraean muck, and fight your way through endless swathes of etymologically-stymied willows. I would like to say that a knowledge of Old English, Latin, Icelandic, in at least one place Greek, and other extinct languages would help the reader - but alas, you also probably would have needed to at least hold a lectureship in AngloSaxon philology at the academic level to really enjoy this book. One gets the feeling that this exclusive group is who Tolkien is talking to, not to the average layman - and one would be right, as this book was basically speeches he gave as Chair of the Old English department at Oxford. Unfortunately, the book was not watered down in the least.

All of this having been said, there were occasional peaks through the dark canopy at the stars. The fight at Finnsburh, as the fragment is sometimes called, was a fascinating example of a switch from heroic tales involving monsters and trolls to an inward-looking piece dealing with internal turmoil and shifting loyalties. It’s rather complicated to explain, unfortunately - mercenaries, loyalty, the breaking of guest traditions, and lots of kennings around death. If it was easy to explain, this book wouldn’t exist; the entire thing is Tolkien (and other scholars) trying to make sense of it, which is most likely why the reconstruction was placed at the end - putting it at the beginning makes it seem like a complete story, where instead the reconstruction process is more like trying to extrapolate what fresh apples tasted like in an 1890’s New York City, by looking at the blown up Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes.

There were some cool linguistic gems hidden in the text (many, really) - for instance, on Hengest:

We must not be mislead by its cognate, Modern German Recke ‘hero, man of valour’, especially as figuring in old tales, and forget its descendant, Modern English wretch ‘unhappy man’. The proper meaning of this word is ‘one exiled, driven out into banishment in alien lands, cut off from his own nome.’

That’s about as cool as a sword pulled from the mire, for me. Or:

fugelas singað, gylleð græghama. This is a clever variation on the conventional animal and bird accompaniment of slaughter (cf Brunanburh 64), combining it with the chill presage of dawn - the cry of birds, the yelp of wolves.

Sometimes, there was even a presaging of how Tolkien may have ended up shaping his own fantasy story. For instance, Finn’s sister Hildeburh has relatives who died on both side in the fallout of the fight at Finnsburgh, and one quote that Tolkien pulls out of another author’s work (several times, as Alan Bliss, the editor, very nicely points out) is instructive:

“the pale figure of Hildeburh…drifts athwart the gloomy background of tragedy like a white dove in a charnel-house.”

If that doesn’t sound like Eowyn, I’ll eat my hat.

I’m not an Oxford don, and my eyesight hasn’t been broken down through years of philological study. But I did study Classics in college, including Old English, and I may have be more inured to the effects of scholarship than others. Even with the books issues, I enjoyed reading it - although I did, at one point, write “Very dense. Hard to read. Fell asleep.” in the margin.

I don’t know if I would recommend this book to anyone else, and I don’t think it is an especially well-written one. But the odds are that I am going to re-read it at some point, because I think there is a story deep in there, and now that I’ve read the whole thing, I’ll know a bit more about what to skim and what to ponder. If anything, that may have been the point of the book - the hundred lines of text we have about Finn and Hengest are intriguing enough to make people stop, spend a decade of their lives on it, and then publish chapbooks like this. I can live in such a world.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.