Here

Reviewed Aug 28, 2017 on The Litt Review.

I’m new to Szymborska’s poetry. My entry was this book, Here, one of her last. According to Wikipedia, she only had around 360 poems in her published oeuvre. The reasoning she gave is that she had a trashcan in her house.

The poems certainly are polished; they’re all tight, self-contained, little things. But of course, all poetry is tight. What makes Szymborska interesting, to me, is that the poems all seem so small in scale. They suggest a wider world, but fill whatever box has been given them, and no more.

No, scratch that.

I have no idea if that is true, but it sounds true. It’s difficult, and almost impossible, to judge and review poetry. You cannot draw a map of it - the map is the territory itself. The poem opens itself up, step by step, and takes you from door to door, filling the rest of the world in on the way. If you try to abstract it, you lose the scent of spring in the air, the name of your neighbor you’re going to see, and the reason you’re walking outside it all. And trying to describe the author is more useless than the poem itself. You don’t know how close the painter stood to the canvas; you can’t tell how close the author was to their words.

What you can describe is your feelings when reading the poetry. I felt that Here was a tidy, little book. I say little because I didn’t dive into the poems, the way I have with others. They didn’t open up for me. The flippant tone of a grandmother seemed to follow me through the pages, and I wasn’t able to focus on where I was going. Some of them stopped me for a while. Vermeer, for instance, was similar to what I would write, freezing a painting in place on the wall, crystalizing the reader in front of a memory of a woman pouring milk. She’s good at this. In Fact Every Poem did the same, for me, making me stop.

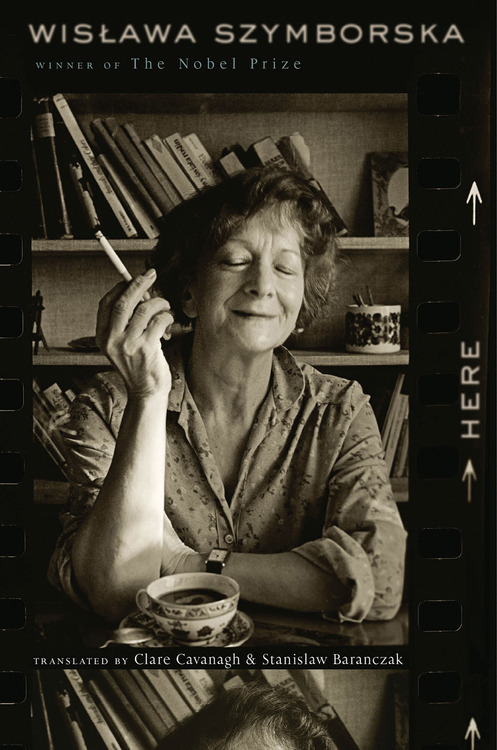

But the majority felt like she was talking to herself, briefly, while sitting over a cup of coffee, looking out into the street. Her phrasing made me feel like I was overhearing something private, something that, if I were to pay attention and ask her to speak up, she would respond “Oh, it’s nothing.” There are no goals in poetry; I can’t ask her if that’s what she meant when writing it (especially as she’s dead, and I can’t understand Polish). But it’s how I felt reading them.

All of the poems, for me, also felt dry, flat, brown. They lacked the deep, wet, green earth that I love. This is probably just because I’ve spent too long reading mountain poetry, too long thinking about plants and moss and ferns growing out of the page. Her poems are human, not animal. To me, that was a loss.

But they are good. I’m looking forward to returning to them, later, with a pencil and an older eye. Soon, perhaps.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.