Sharpe's Rifles

Reviewed Jul 30, 2018 on The Litt Review.

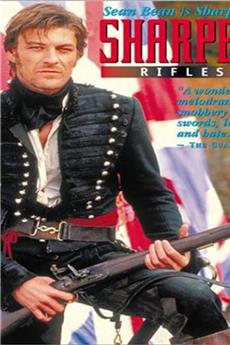

I picked up Sharpe’s Rifles in a small charity shop in the Outer Hebrides, last summer. I read it on a plane to somewhere; I think to Buenos Aires. Richard Sharpe is easily one of my favourite characters from any serial. Bernard Cornwell wrote a dozen odd books for this imaginary soldier from the Napoleonic war in Spain, where Wellington won his Lordship and where a lot of sad young men totally snuffed it. But for me, Sharpe is always Sean Bean, looking into the sunset at the end of every one of the episodes in the BBC miniseries where Bean first became really famous. Even in Lord of the Rings, Sean Bean says “Still sharp” when he cuts his finger on the shards of Narsil. That wasn’t an accident.

Rifles was the first of the books I’ve actually read, I believe. I may have read another a few years back, but I can’t recall at the moment what the title of that was. And certainly, at that time, I wasn’t taking the assiduous notes I do now. I have dozens of quotations in my files for this book, mostly of the mundane “this is what war is” variety. For instance:

The precious cargo had been strapped to a macho, a mule whose vocal cords had been slit so it could not bray to warn the enemy.

Fascinating! I have no idea if this was common, but it is a brilliant way to keep a mule from braying when needed. It’s also brutal, of course, but PETA wasn’t around in the 1800s. My favourite quotations are ones which explain both something meaningful about the past, but also serve to conjure up a beautiful image that helps me feel like I’m there. For instance, with smoking soldiers in file:

These men were now scattered throughout the column as guides, their services abetted by the cigars which Vivar had distributed amongst his small force. He was certain no Frenchmen would be this deep in the hills to smell the tobacco, and the small glowing lights acted as tiny beacons to keep the marching men closed up.

Or, less so, pigtails on the French:

The bloodied face was framed by pigtails.

“Cadenettes,” Vivar said abruptly. “That’s what they call those. What do you call them, braids?”

“Pigtails.”

“It’s their mark.” He sounded bitter. “Their mark of being special, an elite.”

The book itself was a fun, rip-roaring read. It strayed from the episode considerably, but I loved it; Sharpe and his small group of riflemen (sharpshooters) are tasked with a mission to help a Spanish nobleman kill his brother, a Francophile scientist who wants to bring the light of Napoleon to dreary, medieval Spain. Cornwell keeps the moralizing low, largely because the lower-class Sharpe won’t have any of it.

My favorite part of this book was unquestionably the end, with Sharpe manages to kill some important figure, and his immediate reaction is to pilfer the man’s boots.

And with the overalls came the most precious of all things to any infantryman: good boots. Tall boots of good leather that could march across a country, boots to resist rain, snow, and spirit-haunted streams, good boots that fitted Sharpe as if the cobbler had known his Rifleman would one day need such luxuries. Sharpe prised away the razor-edged spurs, tugged the boots up his calves, then stamped his heels in satisfaction. He buttoned his green jacket and strapped on his sword again. He smiled. An old flag, made new, flaunted a miracle of victory, a red pelisse lay in the mud, and Sharpe had found himself some boots and trousers.

That’s right. Victory is at hand, and all the old veteran Sharpe can think about is nice boots. Of course, this reminded me of Mat Cauthon in Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time. I wonder if Brandon Sanderson had read Cornwell - it’s likely. A lot of fantasy authors admire him for his brilliant battle scenes. Sanderson has Mat say this, at one point in the books:

“So you’re using boots as a metaphor for the onus of responsibility and decision placed upon the aristocracy as they assume leadership of complex political and social positions.”

“Metaphor for…” Mat scowled. “Bloody ashes, woman. This isn’t a metaphor for anything! It’s just boots!”

Richard Sharpe would approve.

Words

Words I didn’t know or don’t use enough.

- chasseur, n. a soldier equipped and trained for rapid movement, especially in the French army.

- colback, n. a round hat made of thick black fur. “One was the chasseur Colonel of the Imperial Guard, gaudy in his scarlet pelisse, dark green overalls and colback, a round hat made of thick black fur.”

- shakos, n. a cylindrical or conical military hat with a peak and a plume or pom-pom. “Some men had lost their shakos and wore peasant hats with floppy brims.”

- doghead, n. That part of a matchlock or flintlock gun or rifle that holds the burning fuse or flint and applies it to the gunpowder. “They looked a beaten, ragtag unit, but they were still Riflemen and every Baker rifle had an oiled lock and, gripped in its doghead, a sharp-edged flint.”

- élan, n. energy, style, and enthusiasm “It was because of officers like him that these Riflemen could still shoulder arms and march with an echo of the élan they had learned on the parade ground at Shorncliffe.”

- flensed, v. slice the skin or fat from (a carcass, especially that of a whale). “He stumbled past the flensed and frozen carcass of a horse.”

- Dragoons, n. a member of any of several cavalry regiments in the British army. early 17th century (denoting a kind of carbine or musket, thought of as breathing fire): from French dragon ‘dragon’.

- crapauds, n. toad (French).

- macho, n. a mule whose vocal cords had been slit so it could not bray to warn the enemy.

- guidons, n. a pennant that narrows to a point or fork at the free end, especially one used as the standard of a light cavalry regiment. “The trumpeters were on greys, as were the three men who carried the guidons.”

- rowel, n. a spiked revolving disk at the end of a spur. “They were still a hundred paces away and would not rowel their horses to the gallop till they were very close to their target.” “The stratagem could not be repeated, instead the Colonel would rowel his horse at the last moment so that the black stallion surged into a killing speed that would put all its momentum behind his sabre stroke.”

- picquets, n. a soldier or party of soldiers performing a particular duty “The wounded were laid there while picquets were set to guard its perimeter.”

- enjoin, v. instruct or urge (someone) to do something. “He saw Sharpe about to enjoin him to silence, but shook his head.”

- rookery, n. a dense collection of housing, especially in a slum area. “He had grown up in a rookery where he had learned every trick of cheating and brutality”

- threnody, n. a lament. “He only understood that the words were an insult that would be the threnody of his death as Harper used the stone to crush his skull”

- hidalgo, n. (in Spanish-speaking regions) a gentleman. “An hidalgo, Lieutenant, is a man who can trace his blood back to the old Christians of Spain. Pure blood, you understand, without a taint of Moor or Jew in it.”

- crupper, n. a strap buckled to the back of a saddle and looped under the horse’s tail to prevent the saddle or harness from slipping forward. “The French, always careless of their cavalry horses, drove them until their saddle and crupper soures could be smelf half a mile away.”

- skeins, n. a tangled or complicated arrangement, state, or situation: “The reply came from further down the chasm, somewhere beyond the skeins of rifle smoke that were trapped by the rock walls.”

- benighted, n. in a state of pitiful or contemptible intellectual or moral ignorance, typically owing to a lack of opportunity “Because for once in your benighted life, Lieutenant, I thought an Englishman could do something for Spain.”

- wormscrew “Mad as a hatter, sir. One of the Royal Irish, and they’ve all got wormscrew wits.”

- subvention, n. a grant of money, especially from a government. “We are to make a subvention to the army?”

- aiguillettes, n. One of the ornamental tags, cords, or loops on some military and naval uniforms. “A group of officers had appeared there, their aiguillettes and epaulettes a dark gold in the wintry light, and in their midst were the chasseur in his red pelisse, and the civilians in his black coat and white boots.”

- slew, v. turn or slide violently or uncontrollably “If the coach was to be rescued then the horses would have to be coaxed backwards, slewed, then whipped forward, and that would take time which he did not have, so it must be abandoned.”

- byre, n. a cowshed. “Beyond the passage was a much larger, windowless room, this one a byre for the animals”

- saltpetre, n. another term for potassium nitrate. “The saltpetre from the powder was rank and dry in his mouth.”

- whiting, n. a slender-bodied marine fish of the cod family, which lives in shallow European waters and is a commercially important food fish. “She produced a cask of slated mackerel and whiting, evidence of how close the sea lay, which she distributed among the soldiers.”

- ravelins, n. an outwork of fortifications, with two faces forming a salient angle, constructed beyond the main ditch and in front of the curtain. “It was not a modern fort, built low behind sloping earthen walls that would bounce the cannon shot high over ditches and ravelins, but a high fortress of ancient and sullen menace.”

- gonfalon, n. a banner or pennant, especially one with streamers, hung from a crossbar. “You are looking at the gonfalon of Santiago, the banner of St. James”

- lancet, n. a small, broad two-edged surgical knife or blade with a sharp point; a window or arch shaped thus. “A cold wind, coming through the unglazed lancet window, shivered the candles.”

- rumbustious, adj. boisterous or unruly (British informal). “The did not sing the rumbustious marching songs which could make the miles melt beneath hard boots, but the soft, melancholic tunes of home.”

- musketoons, n. A short musket. “There were ancient fowling pieces, musketoons, horse-pistols, and even a matchlock.”

- blithely, adv. in a way that shows a casual and cheerful indifference considered to be callous or improper. “‘She wanted to Help’, Vivar said blithely.”

- mephitic, adj. (especially of a gas or vapour) foul-smelling; noxious. “As he climed, Sharpe realized that they must have come very close to the city, which was betrayed by the mephitic stink of its streets that seemed to him to be a foretaste of the horror that awaited his men.”

- equably, adv. not easily disturbed or angered; calm and even-tempered. “‘That assumption is your privilege, Lieutenant,’ Coursot said equably, ‘but it will not make me surrender to you.’”

- frog, n. an elastic horny pad growing in the sole of a horse’s hoof, helping to absorb the shock when the hoof hits the ground. “The spikes [of the caltrops] would easily pierce the soft frog tissue inside a horse’s hoof walls.”

- garotte, n. a wire, cord, or other implement used for garrotting. “The tall chair, far from being a throne, was a garotte. On its high back was a metal implement, a collar and screw, that was Spain’s preferred method of execution.”

- dressing, n. size or stiffening used in the finishing of fabrics. “The Dragoons walked their horses, for they wanted to keep their dressing tight.”

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.