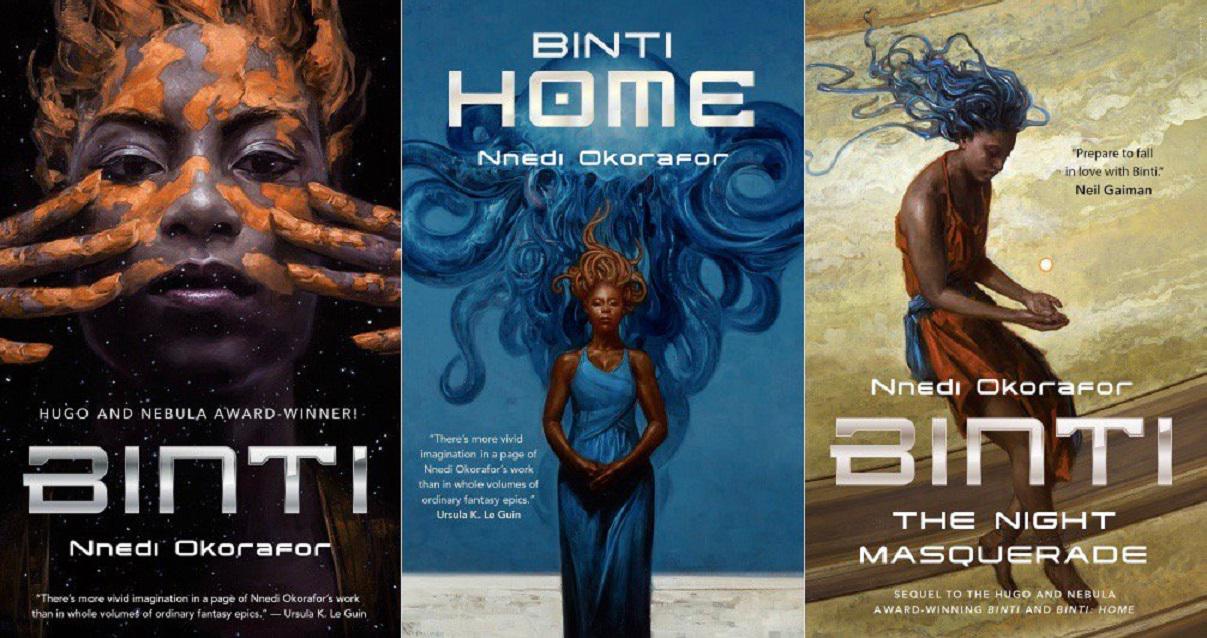

The Binti Trilogy

Reviewed Jun 16, 2018 on The Litt Review.

The Binti books are beautifully crafted, short novellas that combine to form a trilogy of refreshing, earthy power. Ursula Le Guin is quoted on the cover: “There’s more vivid imagination in a page of Nnedi Okorafor’s work than in whole volumes of ordinary fantasy epics.” I agree with this entirely. Neil Gaiman also writes: “Prepare to fall in love with Binti.” The warning was unnecessary. You can’t prepare to love a book, except in setting aside time to read it, and perhaps giving yourself some space afterwards to bask in its warmth for a little while. But the message behind the warning is right; you do fall in love.

The plot is relatively straightforward; a girl from a small, marginal tribe on the edge of the desert becomes accepted at the universe’s most prestigious university, and contravenes her family and her tribe’s tradition of staying close to home by heading out in secrecy to the space port, accepting and leaving Earth.

My tribe is obsessed with innovation and technology, but it is small, private, and, as I said, we don’t like to leave Earth. We prefer to explore the universe by traveling inward, as opposed to outward. No Himba has ever gone to Oomza Uni.

Binti wrestles with this conflict in all three of the books; by exploring learning, she is traveling inward. But physically, she has to travel outward. She is a paragon of her tribe’s values, at the same time as iconoclastically fleeing from its constraints. The books are largely written in the first person, from her perspective, and there is a constant reminder of this paradox. But Binti finds within herself, and her culture’s values, the strength to grow through it.

When I should have revelled in this gift, instead, I’d seen myself as broken. But couldn’t you be broken and still bring change?

She does bring change. Perhaps the main identifying characteristic for Binti herself is the red earthen paste she is constantly applying on her skin, as all of the women of the Himba do.

Our ancestral land is life; move away from it and you diminish. We even cover our bodies with it. Otijze is red land.

It is this otijze, so confusing and alienating to the other human civilization we see most often, that allows her to be spared when an alien race of cephalopods comes into conflict with her and her fellow students. And soon, Binti adapts other identities along with this paste; she becomes something more than human, by the end, adopting names to the point where she states a dozen identities when asked in the final pages. As an intersectional exposé on what it means to be seen from multiple viewpoints, the books are exceptional among genre fiction, which largely shies away complexity in favour of almost stupidly contrasting binaries (elves vs orcs, for instance).

In a large part, these themes are to be expected, because the books don’t stem from the standard science fiction strand of the West. Nnedi Okorafor is a Nigerian-American author, and her roots lie in African science fiction, not American, as she has said many times and as every review of her work will reiterate (she refers to herself as “Nigamerican”, too). Increasingly, reading Binti, it becomes clear that there is a subtler story at work, and I don’t think it would be a stretch to say she is both. The book was, to my knowledge, not written initially in Igbo, but in English.

It is a series of learning, coming to acceptance, and then exploration.

“Look at the grass. Remember what we say?”

“It grows because it’s alive,” I whispered, looking at the red grass. “It grows because it’s alive.”

For me, reading this series was a delight and a pleasure. If I drew any comparisons to Teju Cole, another loved author of mine from a Nigerian-American background, it was only a mental note that both authors are brilliant, and that I want to explore African literature far more.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.