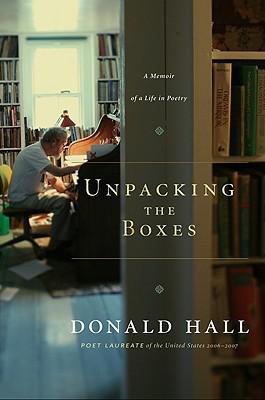

Unpacking the Boxes

Reviewed Jun 15, 2018 on The Litt Review.

Unpacking the Boxes, subtitled A Memoir of a Life in Poetry, was a surprise purchase for me. My sister knew of a bookstore in Seattle that sold only poetry, and, short of something fun or interesting, we decided to peruse the shelves there on a summer morning when I was new in the city. Open Books was a beautiful store, and the small talk with the cashier was more filling than most meals I’ve eaten. I looked for two authors - Jean Genet, who I am not sure actually wrote poetry, and Robert Maccaig, who, being a northern Scottish poet, was unknown to the store. As I couldn’t leave empty handed, I bought two books; Patti Smith’s early work, and this memoir.

I’ve read Letters After Eighty, and was delighted at Donald Hall’s description of living in his body in his old age. His anecdote about being talked to like a child by a guard at the National Mall had me laughing out loud when I read it, and, although I found his poems to be stodgy and metered, I appreciated them, too, and look forward to re-reading them closer. This book was exactly what I predicted it would be; more of the same as in Letters, but going through his whole life and not just a smattering of essays.

It was a pleasure to read. I don’t know why I would turn to memoir at twenty nine as one of my favourite genres, except that it describes in full the long road of someone’s life, and makes my own seem far less stressful considering the unendurable vistas before me. Like Patti Smith’s description of the 70s in New York in Just Kids, Hall was at the centre of his world, one of the kings of the academic poets who dominated the East Coast and literary society for decades. Reading the book, you get a feeling that he deserved it, because he is not sparing when describing the work, the work, always coming back to the work. He appears to have spent his high school evenings writing poetry; his college days writing poetry; and the days after that also writing poetry. In his sixties, following the death of his life’s love, he became bipolar and manic for a few years, and it is only during this time that it seems that he didn’t spend all of his available energy writing poetry. For an amateur like me, it is fascinating to see the work that goes in.

I share a love of poetry with Donald Hall, although I haven’t been fanatical about it since I dropped out of my English degree in Edinburgh (an early recipient of Lyme, I preferred to take long walks than to read another revolting disquisition on a flea. Perhaps I was cursed.) I also share an origin; I too come from Connecticut, and I prefer New Hampshire.

I was all the more Connecticut for preferring rural New Hampshire. (Real New Hampshirites don’t prefer the state; they are it.)

I laughed and laughed at him describing being taken as an East Coast liberal intellectual (which he is), and as an American in Oxford (I sympathised). And I understood, more, when he wrote:

A father who weeps is a gift to his son, but it disturbed me then.

Or:

Sometimes a cousin’s first child was born six months after the wedding; aside from a moment’s tsk-tsk, there were no consequences.

Or:

At Exeter, as I discovered the next year, first-year Latin students ended by doing eighty lines of Caesar a night. When I took the Latin exam for entrance to Exeter, I was asked to translate a passage of Caesar that I had just worked over with my tutor - in my life, one of a thousand crucial pieces of good luck.

Which happened to me with Greek no less than three times (for which I blame having a university degree at all). Or:

We wanted, like Keats, to be among the English poets when we died. The name of poet was glorious for us, as it was for Milton. Shakespeare and Jonson and Dryden wanted to write lines or epics that would live forever. Maybe I should whisper it - it was naïve and perhaps farcical in its self-regard - but so did we.

I agree with this; even with the technical career and my nomadic travels as a backdrop, the majority of what I want is wrapped up in literature. Donald Hall dropped a few one liners that stuck out:

[They repeated the old saw:] To be a poet at twenty is to be twenty; to be a poet at thirty is to be a poet.

And:

Language explains us to ourselves and conceals us from ourselves.

But the majority of this book wasn’t so much about this year, or that; about this poet that he met, or about the time he met the ‘saturnine’ Chomsky or found himself on a Republican donor panel by accident; rather, the book covered a life. Having read it, I am struck by that peculiar feeling that only seems to occur when listening to the old discuss the long years they’ve lived. I’m glad I took the time, and I look forward to reading this book again.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.